He sits behind a desk, his back to a computer. A low cabinet next to it is stacked with books and files. A wood-panelled wall camouflages the door to the room where his two secretaries work. A teak table for eight stands four metres from his desk, a jade dragon jar in the middle. Lee works in this office six days a week, from about 10 in the morning to 6:30 in the evening, when he puts his work aside for his daily exercise in the Istana grounds. He has been known to come back to the office on Sundays and public holidays.

He is about 1.8 metres tall, and slim. His trousers, which are usually in light hues, are loose, and he tugs at the waistband frequently. He is at least 10 kilograms lighter than when he was in his forties. His shirts are well-pressed though well-worn, and he wears a windbreaker, usually beige, when he is in the office.

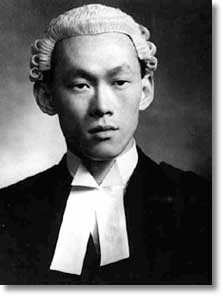

At 74, his hair is white. The once wiry black mop has thinned considerably over the years, accentuating a broad, high forehead under which small, piercing eyes stare. His face is pink in tone, the skin mostly unlined, though tiny creases crisscross the skin on his eyelids. His nails are neatly trimmed.

Even in a private setting, he is a forceful personality. His facial expression changes quickly and his hands often chop the air to emphasise a point. His voice rises and falls according to his emotions. He is quick to show impatience, and slow to smile. He has never suffered fools lightly. Who is this man who, more than anyone else, has shaped the history of modern Singapore? Who is the person behind the personality Singaporeans regard with awe, respect, love, fear or hate? How would he describe himself? How does he see his 40 years of political life? What is his role now? What is his family life like? And what are his dreams and fears? Lee revealed his personal life in these interviews with the authors, weaving in events that took place 40 years ago as if they had happened only yesterday.

On one of these voyages, he met Ko Liem Nio in Semarang. They married and he brought her to Singapore.

He moved up the company and eventually possessed power of attorney over the concerns of Sugar King Oei Tiong Ham. His fortunes rose with Oei's. By the time Kuan Yew was born on Sept 16, 1923, Hoon Leong was head of a wealthy family, though its fortunes suffered somewhat during the Depression of 1929 - 32.

As was the practice in those days, the marriage between Lee's parents, Lee Chin Koon and Chua Jim Neo, was an arranged one. Both came from successful middle-class families and were educated in English schools.

Lee's maternal grandfather owned the former Katong market, rubber estates at Chai Chee and a row of houses next to the present Thai embassy in Orchard Road.

Those were the days when successful Chinese businessmen working within the colonial system in Singapore were able to make vast fortunes mainly in trading and property development.

The Depression took its toll and both Lee's grandfathers' wealth declined considerably.

Lee's father worked first as a storekeeper at Shell, the Anglo-Dutch oil giant, and was later put in charge of various depots in Johor Bahru, Stulang and Batu Pahat. But it was his mother, Jim Neo, to whom Lee attributes much of the family's success in overcoming the financial difficulties.

By then, the family had a house in Telok Kurau. For Lee and his three brothers and a sister, these were carefree days. But even though, by his own admission, he did not work very hard in school, he was always there at the top of the class.

The pace quickened somewhat after he enrolled at Raffles Institution; Lee emerged top Malayan boy in the Senior Cambridge examinations.

His decision to become a lawyer, which would have a profound effect on his political activities later, came about from purely pragmatic considerations.

"My father and mother had friends from their wealthier days who, after the slump, were still wealthy because they had professions, either doctors or lawyers.

"The doctors were people like Dr Loh Poon Lip, the father of Robert Loh. The lawyer was Richard Lim Chuan Ho, who was the father of Arthur Lim, the eye surgeon. And then there was a chap called Philip Hoalim Senior. They did not become poor because they had professions.

"My father didn't have a profession, so he became poor and he became a storekeeper. Their message, or their moral for me, was, I'd better take a profession, or I'd run the risk of a very precarious life.

"There were three choices for a profession -- medicine, law, engineering. We had a medical school; we had no law school or engineering.

I didn't like medicine. Engineering, if you take, you've got to work for a company. Law, you can be on your own, you're self-employed. So I decided, all right, in that case, I would be a lawyer."

"They (the Japanese) were the masters. They swaggered around with big swords, they occupied all the big offices and the houses and the big cars and they gave the orders. So that determines who is the authority. "Then, because they had the authority, they printed the money, they controlled the wealth of the country, the banks, they made the Chinese pay a $50-million tribute. The Chinese merchant community, you need a job, you need a permit, you need to import and distribute rice -- they controlled everything.

"So people adjusted and they bowed, they ingratiated themselves, they had to live. Quietly, they cursed away behind the backs of the Japanese. But in the face of the Japanese, you submit, you appear docile, you're obedient and you try to be ingratiating. I understood how power operated on people.

"As time went on, food became short and medicine became short. Whisky, brandy, all the luxuries which could be kept in either bottles or tins -- cigarettes, 555s in tins -- became valuables. The people who traded with the Japanese, who pandered to their wishes, provided them with supplies, clothes, uniforms, whatever, bought these things and gave them to the officers.

"And some ran gambling farms in the New World and Great World. And millions of Japanese dollars were won and lost each night. They collected the money, shared it with, I suppose, whoever were in charge: the Japanese Kempeitai and the government or generals or whatever. Then they bought properties.

"In that way, they became very wealthy at the end of the war because the property transactions were recognised. But the notes were not.

"Because people had to live, you've got to submit. I started off hating them and not wanting to learn Japanese. I spent my time learning Chinese to read their notices.

"After six months, I learnt how to read Chinese, but I couldn't read Japanese. I couldn't read the Katakana and the Hiragana. Finally, I registered at a Japanese school in Queen Street.

"Three months passed. I got a job with my grandfather's old friend, a textile importer and exporter called Shimoda. He came, opened his office. Before that, it was in Middle Road. Now it's a big office in Raffles Place. I worked there as a clerk, copy typist, copied the Japanese Kanji and so on. It's clerical work. "But you saw how people had to live, they had to get rice, food, they had to feed their children. Therefore, they had to submit. So it was my first lesson on power and government and system and how human beings reacted.

"Some were heroic, maybe misguided. They listened to the radio, against the Japanese, they spread news, got captured by the Kempeitai, tortured. Some were just collaborators, did everything the Japanese wanted. And it was an education on human beings, human nature and human systems of government."

THE SCALES FALL:

WHEN the war ended, Lee had to decide between returning to Raffles College to work for the scholarship, which would fund his law studies in England or going there on his own steam.

Britain, land of his colonial masters and the epicentre of the vast, if fast declining Empire, might have elicited from a subservient subject of a distant outpost, 11,000 km away, the reverence it once undoubtedly deserved. But war-torn Britain of 1946 was a different proposition altogether.

For Lee, the first few months were disorienting, hectic and miserable. Arriving in October, he was already late for college admission. But being first boy in the Senior Cambridge examinations for all Malaya helped. The dean of the Law Faculty at the London School of Economics was suitably impressed and Lee found himself thrown into the rough and tumble of undergraduate life in the imperial capital, an experience he found thoroughly unpleasant.

With the help of some friends in Cambridge and a sympathetic Censor of Fitzwilliam House, he got himself admitted and moved to the university town.

Lee went on to distinguish himself in Cambridge, obtaining a rare double first. But though his top priority was his studies, something else much more intense was stirring in him.

It was in England that he began to seriously question the continued right of the British to govern Singapore.

The Japanese Occupation had demonstrated in a way nothing else could have done that the British were not a superior people with a God-given right to govern.

What he saw of them during those four years in Britain convinced him even more of this. They were in it for their own benefit, and he read all about this in their own newspapers.

"Why should they run this place for your benefit? And when it comes tumbling down, I'm the chap who suffers. That, I think, was the start of it all.

"At that time, it was also the year following my stay in England and insurgency had started (in Malaya) and I had also seen the communist Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) marching on the streets.

"I would say Japanese Occupation, one year here, seeing MPAJA and seeing the British trying to re-establish their administration, not very adept ... I mean the old mechanisms had gone and the old habits of obedience and respect had also gone because people had seen them run away.

"They packed up. Women and children, those who could get away. We were supposed, the local population was supposed to panic when the bombs fell, but we found they panicked more than we did. So it was no longer the old relationship.

"I saw Britain and I saw the British people as they were. And whilst I met nothing but consideration and a certain benevolence from people at the top, at the bottom, when I had to deal with landladies and the shopkeepers and so on, it was pretty rough.

"They treated you as colonials and I resented that. Here in Singapore, you didn't come across the white man so much. He was in a superior position.

"But there you are in a superior position meeting white men and white women in an inferior position, socially, I mean. They have to serve you and so on in the shops. And I saw no reason why they should be governing me. They're not superior. I decided, when I got back, I was going to put an end to this."

This page has been visited

to MANSION'S ENTRANCE at Tripod!

to MANSION'S ENTRANCE at Tripod!

HERMAN LEONG

hermanl@cyberway.com.sg

, SINGAPORE